At Ocean Falls, a ghost town on the central coast of British Columbia, 35 mW of power drains away in to the sea, unused. In this post, I will take this as symptomatic, in a spirit of autumnal regret.

1.

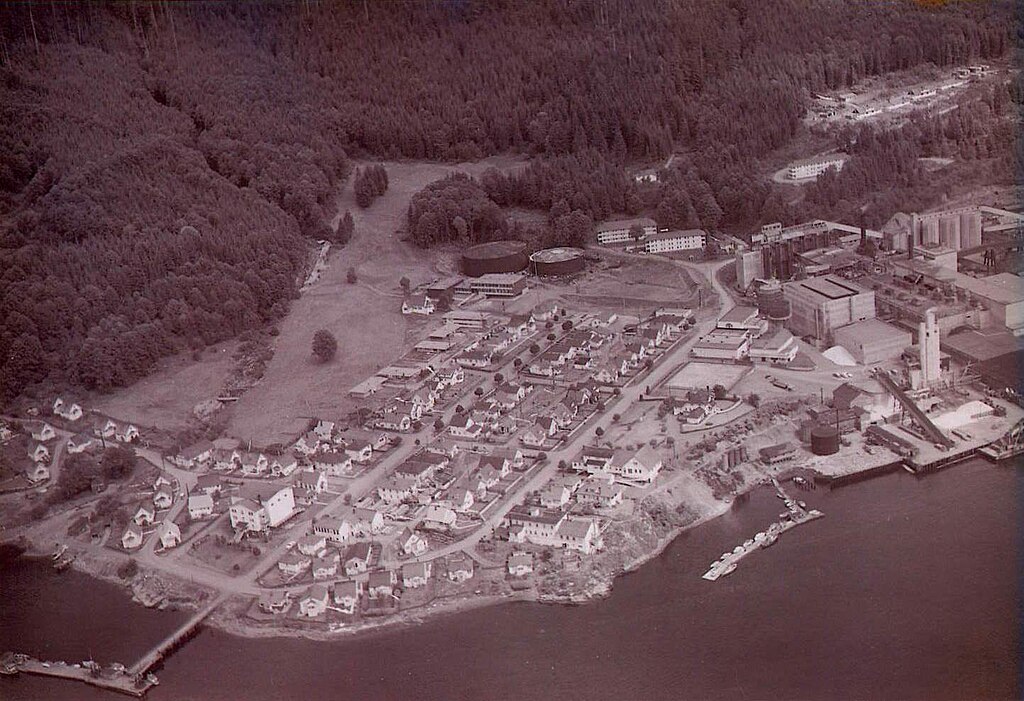

Back up: I grew up, it bears repeating, in a small town built to service a sulphite pulp mill hurriedly erected during World War I at the ass end of creation to hear the local kids talk.

Here: let's look at the great picture that someone scrounged up for Wikipedia again:

It also bears repeating that the townsite does not look like this any more, that the buildings were all torn down and a new site in early-60s high modern was built a ways down the inlet. The only thing remaining is the meadow above the town, which is a golf course. Surreal, I know. For me, this picture is one of nostalgia for places never seen, a mood for which there must be a German word. This is the Port Alice of the deep past, a community of migrant workers and old-time families sleeping in their isolation from the world from 1917 to the early 1960s, one of many such.*

Today, the subject is the dates. I am going to try to pinpoint the moment when the tide of modernity reversed, the moment when the end of the age of grass asserted itself.

Port Alice is still going, survived the end of grass. Port Alice, like the other pulp mills on the coast, was built next to a convenient source of hydroelectric and hydraulic power, and this is quite an advantage. Add to that that people are even investing in making new rayon these days, and with the collapse of fibre demand from newsprint mills, the future is positively bright --for the mill, anyway. It's never going to support the number of workers, hence town population, of the 1970s, however. When the town was growing, reluctantly, haphazardly, as those who might have wanted to build their own homes on the townsite looked over their shoulders at the painful death of: Ocean Falls.

2.

Port Alice was built near a convenient source of water power, and, of course, a great many trees, just like Ocean Falls. It turns out that the trees are the important bit, although neither mill was graced by an excessive supply of reserve fibre, and this does not sufficiently explain why Ocean Falls failed, and Port Alice didn't. (The nature of the product probably explains more, but this is not the place to talk about the death of the newspaper, which in any case will be back as soon as hackers and general neglect have finished killing off the Internet.)

Both the politics and economics of harvesting the trees is remarkably complicated, and if you ever hear an environmental activist talking about the "last remaining first growth forest on the B.C. coast," you should then imagine a north-of-Skookumchuker saying, in his Bob-and-Doug-Mackenzie tones, "I wish."

The truth is that there isn't enough money in the world to get at most of the trees in the central coast, where the Coastal Range comes down to the sea, though the forests there might yield six million cubic meters, by the provincial government's rule of thumb.

|

| Source Do not expect this "virgin rainforest" to be violated by mean old loggers any time soon. They could --but they'd have to capitalise a road to it, first, so that they could get the highlines in. |

Also, a few retired boaters drop small change in local marinas. Sounds like a business plan!

If it feels like I've dropped northern Vancouver Island from the discussion and moved on to the Central Coast without much context, let me fill you in by locating the ghost town of Ocean Falls for you:

There you go. The driving directions from Bella Coola, British Columbia

| Nuxalk Nation |

to Ocean Falls. (Although they're more readily summarised as "put your car on the boat. Take it off when you're told.") Bella Coola is an ancient centre of civilisation on the central coast, built at a river mouth with convenient access to the central plateau. Alexander Mackenzie, making his fabled first overland crossing "from the Canadas" reached the Pacific Ocean at Bella Coola because of this route, an ancient grease trail for moving fish oil inland. (The culinary sensibilities of Neolithic peoples differ in some respects from our own.) Now there's a road, famous for descending the 1500 meters of elevation difference from the Chilcotin plateau to the coast in a road distance of 43km.

It has a great deal more reason to exist than Ocean Falls, but it is still a struggling hick town of 1400 people.

From geographic trivia, or for that matter the Mandelbrotlike character of the coastline, you might be able to guess why the road does not continue to Ocean Falls. If you're not feeling like solving riddles, I'll just say that the road would be too long, and go over too many hills and bridges to be economical.

So...Ocean Falls:

If nostalgia for places you've never been to is your thing, "the home of the Rain People" has you covered. It's probably a bigger place on the Internet than it ever was in real life. This panorama of the town at, or near, its peak is one of more than 4000 images at the largest, but far from only dedicated site. A closer inspection of the site might raise a question: why all the nostalgia?

See? All the charms of Siberian Industrial Gothic, except built in wood instead of Stalinist concrete and suffering under 172 inches of rain a year instead of -40 temperatures.

Though, to be fair, this is what they had to work with:

And this is what they've managed to make of it.

Love, time and hard work have done their work, and had the pulp mill not shut down in 1980 after eight years of struggle, it would all look like this today.

Though, at the time, it had a long way to go. Not surprisingly, the town's tiny professional set of teachers, doctors, police officers and senior tradespeople humped down the main logging road to the nearest patch of flat land and built a small community of privately-owned homes in Martin Valley. The brief Wikipedia article notes that "in most cases the company offered a buy-back guarantee." Even at its peak, it was fairly obvious that the town would vanish if the mill did. I doubt that we're going to get much more of an explanation than that: "Scenes from the class struggle at Ocean Falls" does not work well with the general theme of nostalgia. (We're not going to get a picture of any Ocean Falls Chinatown, either, and for the same reason. Or an explanation for why the official town history says that the first church services were held in the school basement in the 20s, and the town archive has a picture of the consecration of the first Roman Catholic church, in 1910. We all know, without wanting to say, who were served by coastal mission churches in 1910.)

Had the town endured, talk was that the whole townsite would have been relocated up to Roscoe Inlet, where the precipitous landscape in the first photo after the cut is found, but also this nice bit of flat land:

Just to orient you:

The road distance here is 16 kilometers. It was never going to be. The owner never saw the logic of upgrading the mill so frantically brought to full production in 1945. The closure of the mill was announced in 1972. Politics intervened, and the story dragged out for another agonising eight years, with the final closure sending a very clear signal to the other mill towns that if they failed to make their own operations economical, the province was not going to step in.

It was World war I that really made Ocean Falls. Logging had begun there, and Pulp milling elsewhere, on the coast more than a decade before, but Swanson Bay might as well be the Lost City of Opar for all we know about it, and the early days of Ocean Falls are almost as obscure. The war brought demand for aviation-grade spruce, nitrocellulose, and even plain old paper. It made the economic logic compelling. The pulp mills at Port Alice, Ocean Falls both began operations in 1917. Even in faraway British Columbia and in the most unglamorous of fields, the stimulus to production triggered by the insufficiency of means on the Somme was felt.

Enough burying the lede. This is the hydroelectric dam at Link Lake, hiding behind the fold of the hill in the panoramic shot above, and giving the town its name.

| Robert Berdan at Canadian Nature Photographer |

The Link Lake dam today generates 2 MW, which is mainly used to overcome line losses on a long transmission route to Bella Bella. It has installed capacity for 11, and is allegedly capable of delivering 35. This is not exactly a lot. In its salad days, the dam did not even enough to process the 350t/day installed capacity of the old pulp mill, which therefore burnt hydrocarbons of some kind, and heated the townsite with steam. Another way of putting it is that the Dalles Dam in Washington state has, to compare likely equally optimistic estimates, a claimed overload capacity of 2000MW.

The point here is not that Link Lake is a vast resource left to roar unhindered into the sea. It's that it's a significant one. We just can't come up with an economic way of using it. At this point, it's easy to just point your finger at capitalism. In a planned economy, the state would take over Ocean Falls and run it, so that the Link Lake power generation capacity doesn't go unused.

But we tried that: the limit was in allowable cut, so that timber diverted to Ocean Falls was not available to sustain production and jobs at other mills. Unbridled capitalism built Ocean Falls, and Port Alice, and Powell River, and the many other pulp mills that joined them in the wake of the Second World War. The reason that the incoming socialist government took over Ocean Falls in 1973 and tried the whole "planned economy" thing was that unbridled capitalism had led to a community of 3500 people there as of 1950.

If you're one of the more than 99% of the population who lives in an area with a population density of closer to 100 per square miles than 1 per 100 square miles, you're going to have to adjust your expectations, but 3500 people is a lot of people by old coastal BC standards. Just saying that number, conjuring a world like in Archie comics. Once you understand that the pulp mill community was integrated by the circulation of skilled tradesmen from town to town, you understand what Ocean Falls signifies: a mythic 1950s when a civic booster could imagine a town that would go on growing and expanding, adding houses and neighborhoods, perhaps even, dream of dream, a store that sold comic books.

| Note that someone has taken the trouble to ship in a car so that he can drive into town from Martin Valley. It's the only road, and it's three miles long! |

To be clear here: had there been a network of roads radiating out from Ocean Falls up the valleys and mountain torrents, the issue of tree farm licenses would have never come up, because it would not be that hard to push the roads far enough to give access to enough timber to make abandoning the town the wrong option. That such a network of roads is economically unimaginable is the point here. It would have followed naturally from the spread of the community into the hills and valleys. So the point here is that this did not happen. The townsite did not move to Roscoe Inlet, in short.

3.

If Ocean Falls is a ghost town, Powell River is thriving, at least, relatively speaking. So somewhere in the gap between the two is the dividing line between success and failure.

Powell River is a big mill, bigger than Ocean Falls running flat out, although it is not even close to that today. Let's do the map-and-photograph thing to get a sense of the community:

i) Seattle to Powell River. Notice that the map jumps two ferry routes and leaves out a "great circle route" that takes you back to Seattle on two more, so if you like taking the ferry, I actually recommend this as a vacation plan, unlike the Bella Coola route, which should only inspire you if you like really, really dangerous highways, and, if you do, you should probably visit New Denver first.

ii) Powell River, the immediate surrounds:

The lack of contour shading around Powell River should not be taken as implying that it is flat as such. In this map, contour shading is reserved for areas with elevation relief changes in line with sea-level-to-six-thousand-feet-in-one-unbroken-climb.

Here's how the Chamber of Commerce wants the Wikipedia user to imagine Powell River:

The basic hydraulic geography is familiar enough: a hanging valley, filled with a lake, which is connected to the sea by a gorge, so someone built a mill next to it to exploit all the free power.

It's not quite as spectacular a head of water as at Ocean Falls, in that, while "the Sunshine Coast" might be a tad optimistic, Powell Lake is not quite so bountifully replenished with water as Link Lake.

It is, however, larger. More importantly, amongst the great mass of random cratons swept up by the westward advancing continent, the one on which Powell River is located is relatively flat. There are more, accessible natural reservoirs to dam and extract power from, and more accessible forest land to harvest.

So now we know why Powell River survived, and Ocean Falls did not.

Survival is relative, though. Powell River is a hick town, no doubt about it. This is a Google Streetview from the main highway:

People build very nice houses right along the highway. Admittedly, they give themselves nice setbacks --why not, it's not like land is expensive-- but they don't build fences, either. There's no particular reason to do so. The city's official population is less than 14,000, and I doubt that people living outside the municipal boundaries add very much to that. Not many people in a lot of space adds up to not much highway traffic.

Here's another image grab, part of picture that Georgia Combes was nice enough to upload to Panoramio.

Haslam Lake is nothing special, just another little mountain lake. I've never been there, and I don't expect that I ever will. I doubt that you, the reader, ever will, either. I suspect that it's described in town as a "popular hiking destination--" you can see the trail in the foreground. The cut blocks indicate that the lake is girded by a logging road. My point, such as it is, is that, to a casual eye, a more densely population area would see some meadows cut out of the forest. There aren't. There could be. It's just that no-one is going to make money selling wool, much less mutton or milk or beef. This is what I mean by the end of the Age of Grass. We've far more pasture than we need. Powell River's hinterland is more useful than that of Ocean Falls because it produces more timber and more electrical power, and it does so because it is easier to access than that of Ocean Falls. Both would have been developed for their own intrinsic value in a day when we lacked enough pasture, instead of, as today, having too much.

Powell River pulp mill is operating at something like a third of its capacity these day, yet the town has not failed. The Wiki article blathers on about alternative economic bases in the form of eco-tourism and whatnot, but the basic fact is that human communities live for themselves. Truck and barter, you know the drill. Though for how much longer is open to question as the young folk move away, like an ebbing tide, for lack of opportunities.

This is the point I want to come around to: at the turn of the last century, modern industrial civilisation reached the coast of British Columbia in the form of the pulp-and-paper industry. The tide of modernity reached its height at Ocean Falls. The boosters who cite a population of 3500 in 1950 suggest that the town's peak of population was 3900. From the phrasing, I suspect that the actual census number of 1960 is below 3500, and the common talk from the raging days of the dying of the town of "more than 5000" shows us that this is a species of wishful thinking.

There was a moment, then, when the population of the community of Ocean Falls reached 3900 people. But it it is a moment in a past future never to have been.

Here's the future that Ocean Falls was getting ready to meet in 1950. The year that the children of the Baby Boom would turn 10, and gather around this car that for the moment only exists to obviate an hour's walk to Martin Valley. It is 1956, in that mythic future past of 3900 people. The children in that picture have six years to go to sweet sixteen, and in that year, they, and the town from which they come, will emerge from its chrysalis into a continent awakening to the colossal optimism of youth. The road will come, and the the future will begin. This is the never-to-have-been moment that the Rain People revisit on the Internet, and sometimes in real life, from all the places out in the world where they live today. The real world that never came to Ocean Falls.

It was never going to happen. We know that now. The whole notion is beyond surreal in retrospect. Sometime in the two-decades-and-a-bit between 1950 and 1972, it will dawn that Ocean Falls will not keep on growing, that 3500 is a peak, not a point on an ascending line, that homes would not continue to spread along the slopes, that farms would not spring up on the bottoms, that forest would not give way to grass, that these mountains and their meadows would never be put to grass.

This was a local thing. Ocean Falls was consumed with the agonies of its own death, believing, hope against hope, that a socialist government could reverse the tide with a magic wand. The other pulp mill communities of course wanted Ocean Falls to succeed. At the same time, if the limit really was allowable cut, we could either fantasise about higher sustainable yields in the accessible forest lands, or accept that Ocean Falls succeeding meant less chance of our towns enduring; that we, instead of they, would see our childhood homes bulldozed and given back to the forest. That we had to fear that Ocean Falls was the first bit of beachcomb, stranded at highest tide, and that the question was, how much more driftwood would be stranded by the time we hit low tide?

Because, and I repeat: we're letting 35 megawatts just pour into the ocean because we can't find a way to use it. We can't. Land, power, opportunity (and probably timber) are going begging, and it is beyond our strength to reach out and take them.

In a world where it is fashionable to either fear a future where robots take our jobs, or imagine a transhuman utopia where we become the robots (that is, our brains do, or whatever the hell Ray Kurzwell is saying today), it's contrarian to fear instead that deurbanisation is our future instead, that, far from expecting the tide to reverse, we need to wonder if we have misplaced the Moon. Call it the consequence of growing up in a town haunted by the doom of Ocean Falls.

Or call it a plea for more economic stimulus. Ahem: policy makers. This whole "oil economy" thing broke how we do things. A fix might be in order, and the sooner the better, because it will get worse, probably until the moment when we need all that grass again, and the standard of living back in those days was lacking in a lot of the nice things that I, personally, would like to keep.

*Just to be clear here, Port Alice, and the actual Ocean Falls, are only the world of Beaver Cleaver if we imagine the set of Leave it to Beaver populated by "Chinese, East Indians and Indians," as they used to say, because everyone knows that people with pigment in their skins aren't real Canadians. Oddly enough, the pigmented people also managed to have no descendants, as a look at the self-reported racial statistics for small town British Columbia communities will tell you at a glance. Yet Dong Chong built the grocery store tin Port Alice, and Herb Doman bought it when ITT gave up the ghost. the Indians are a bit more complicated, you might imagine me thinking..

**A better eye for cars will probably come up with a better estimate than "1956" --frankly, 1965 is more likely, but less elegaic.

***We'll leave aside the fact that the modern community is served by a car ferry, because it gets in the way of a perfectly good metaphor.

There's the clever people at NH3 Canada, who have, or at least who claim very publicly to have, a device that converts air and water and electricity into ammonia at 70% efficiency.

ReplyDeleteThat's an obvious use for your 35 MW, since ammonia -- with no carbon and half the energy density of gasoline -- goes, aside from into the ground as fertilizer and refrigeration systems, into a bunch of fuel cell technologies, all of which are comfortably more than twice as efficient as internal combustion engines. It's also something we understand how to handle, and can put into tanks and ship.

(I suspect the long term plan would be big ocean-going sailing ships that drag their props to generate the electricity, and come back into port when they're full. But for getting-started purposes? One could do a lot worse than a 35 MW hydro dam.)

A firm called Boralex acquired the Link Lake plant in 2009 along with "two other hydroelectric properties in the region with a total generating capacity of 10 mW." The fact that Boralex feels it necessary to buy what are probably run-of-the-river projects out in the hinterlands suggests that they're eventually going to try some kind of carbon-fixing-stuff-making technology --or, more likely, flip to others who will take on the risk.

ReplyDeleteThe fact that this happened in 2009, and we're still speculating about what might be happening five years later is --well, I suggest that it's a symptom of this world we live in now. I mean, there's nothing particularly high tech about a Haber tank. An all-electric Haber process plant might not make money, and 20(?) 25(?) (45(?) mW might well be below some crucial break-even point....

Of course it is. What am I even saying? People look at the money required and the revenue streams that will come out, and even with the carbon capture angle worked in, conclude that's it not worth the bother. Ammonia is made from natural gas feedstock by burning natural gas for energy, notwithstanding the carbon produced, because, you know, the economic case can't be made for investing in any new ammonia-manufacturing infrastructure, never mind radical new technologies.

Shorter: mW at the end of the world? Meh. I get a better return parking my money in Treasuries.

Which strikes me as the problem here. (I like, by the way, that in the 1919 number of Popular Science that popped up at the head of the Google search that I dilatorily executed to find an estimate of the current requirements of a Haber plant, the next article following is on "Extracting Rheumatism Through the Skin." We've come such a long way in some areas, and so little in others...

Greed isn't a virtue.

ReplyDeleteThe last three hundred years have involved trying to make greed a virtue, by any means or all, and it doesn't work. (You can push it back further than that, by noting that the Spanish conquest of Central and South America was chiefly driven by men of desperately poor upbringing whose sole goal was to not be poor.)

There's a big problem in that the current ruling elite doesn't want to stop being the ruling elite, and necessary (and inevitable) economic change means they will stop, but for most of them "after I'm dead" is more important than anything else.

The good side is that the technical problems are pretty much all solved. The social problems, well, this is oddly reminiscent of the Bronze Age collapse, isn't it?

Or the Roman, or any number of others in prehistory.

ReplyDeleteGood thing we've learned from bitter experience what to do in a situation like this!

Glad to see one of my Ocean Falls pictures being used here. Front Street - 1974. My family lived there from 1960 - '67, and I again in the summers of 1975 & '77. Great town!!!

ReplyDeleteThanks for posting it in the first place, John. Ocean Falls is gone, like so many lost towns of the Coast. But, uniquely, it lives on on the Internet thanks to the Rain People.

Delete